Day 16: Villambistia → Burgos (43.12 km)

In the morning, my feet still stubbornly refused to go on. I looked up the timetable for the bus and hobbled across the road to wait, accompanied by a Kiwi named Barry. The bus stop was an abandoned, disintegrating booth covered in graffiti. Half an hour after the scheduled pickup time, we were on the verge of maybe, possibly, considering giving up and walking the 1.5 km to the next town, when the bus finally arrived. I bought myself a ticket to Burgos, the next major city, because I couldn’t risk ending up somewhere that didn’t have a pharmacy. As bad as I was hurting, two things instantly made me feel a lot better: several friends got on the bus in the next town, and it rained. Thus all FOMO was obliterated, and I felt no sense of loss for those 43 km.

In Burgos, we picked up some maps at the tourist office, took pictures outside of the magnificent cathedral, then looked for our respective albergues, hostels, and hotels. (I think Geraldine, Carrie, and Michelle were there but no one can find the group photo.)

I put my backpack in the queue for the municipal albergue, and we met up for breakfast in the café across the street while waiting for check-in time. It ended up being one of the nicest municipal albergues I stayed in, with cubby-like bunkbeds that gave a little more privacy and blocked a lot of noise. Each little block even had its own sink. My bunkmate was a nice lady with a comforting presence named Foster, originally from Australia, now living in London.

Next stop was the pharmacy, where they told me nothing could be done for my blisters other than prevent infection and rest. In other words, no walking tomorrow either. I bought some antiseptic and walked back to the albergue in tears to hand-wash my underwear. C’est la vie! Foster caught me crying and was very sympathetic.

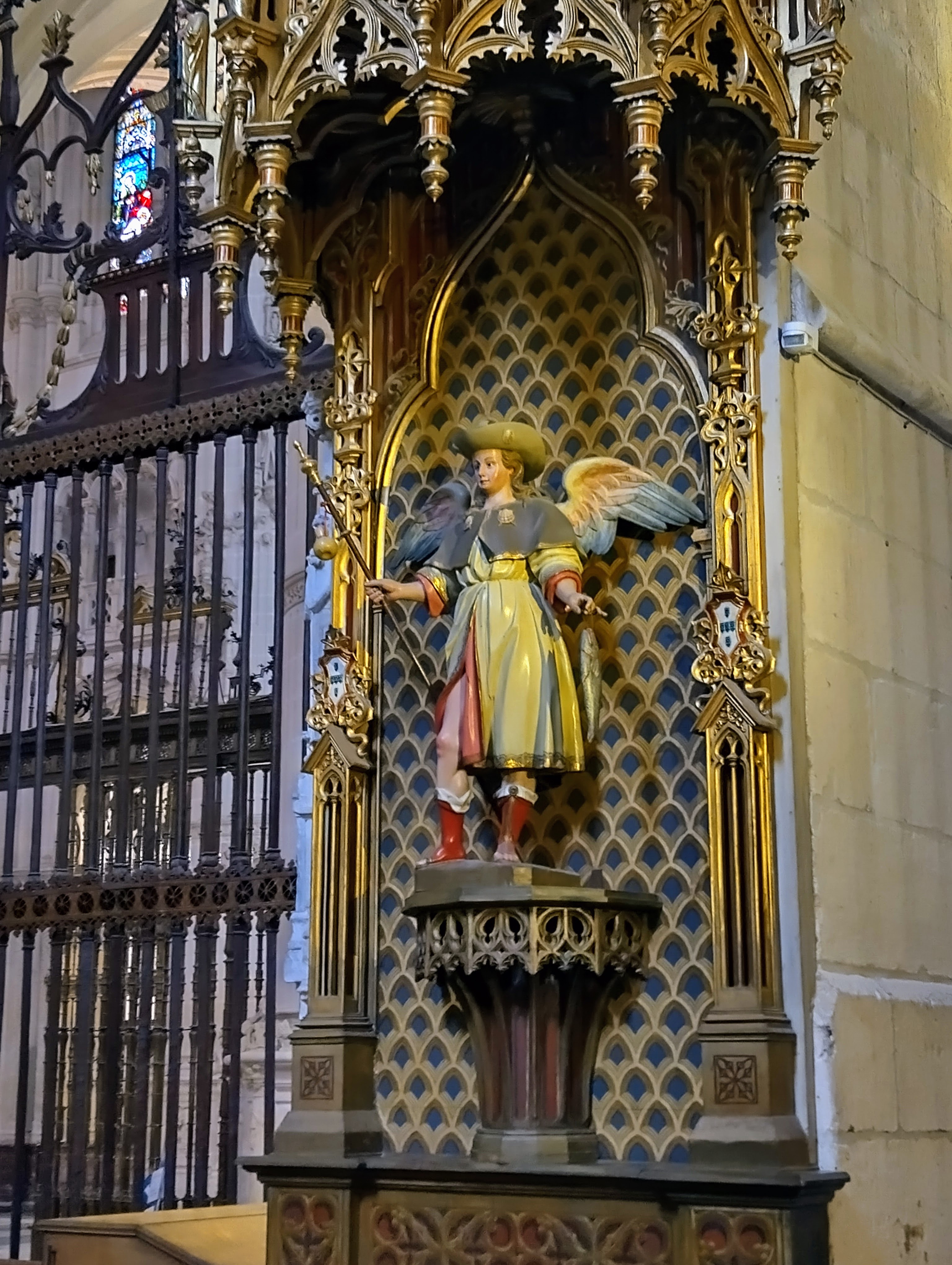

Blisters or no blisters, the cathedral was too tempting to resist. I spent several hours hobbling from bench to bench to sit and admire the intricate stonework, carvings, paintings, and various gold thingamajigs (I believe that’s the technical term). Eunseok eventually found me there. We’d seen a lot of cathedrals together at this point, and were starting to identify some common trends, but this one went above and beyond. He remarked, “Why do rich people love tiny dogs?” vis-à-vis the many crypts of royalty with dogs at their feet. The highlights for me were Leonardo da Vinci’s Santa María Magdalena, cowgirl angel, and monkey with a shotgun.

More friends arrived throughout the day. One of those friends was Julia. I’ve alluded to her only a couple times in this blog so far, but these minor mentions do not reflect the larger presence she had in my thoughts. She was the pilgrim who came alone instead of with her husband because he had passed away; she was the pilgrim who I lit a candle for in Estella; she was the pilgrim the encouraging messages were sent to. Her introduction at Orisson had hit me like a barbed arrow that wouldn’t come out, and even though we didn’t spend much time together, it felt very important to me for her to have a good Camino. The last time I had seen her was in the Pyrenees when she enlightened us that some little structures we kept seeing were for storing hay—she grew up on a dairy farm, if I remember correctly. I thought about her often as I walked and felt instinctively that she needed some help. Luckily, Kim Kimmy had done what I’d failed to and gotten her number. We added her to the group chat when I was back in Estella. She had been struggling a little further behind most of us and almost decided to go home, but here in Burgos, an oasis of white towels and bathtubs, she sent a message saying that “life is wonderful”.

Plans for everyone to meet for dinner were made and cancelled due to exhaustion (Troy had walked 38 km!), illness (a nasty cough was going around), and preferring a warm shower to going outside in the cold (duh). All totally understandable, and reinforced my perspective that not making plans at all is the best way to go.

Dinner ended up being just me and Kim Kimmy wedged into the tight corner of an irregularly-shaped restaurant. We split black sausage and a complicated tortilla that inexplicably came in its separate component parts and talked about the Camino and life. One of the big topics was how people try to put you in boxes. It was something she and I had in common and a prevalent theme of my Camino. Often when I meet people—and you meet a lot of people on the Camino—I find that they try to figure me out, label me, or “put me in a box”. That’s only natural, of course. The problem is most people don’t fit into any one box. Race is an easy example, but this applies for many other things too. You’d be surprised how often people ask me where I’m from and refuse to accept the answer. Personally, I don’t think that is very polite. When I met some pilgrims with thick Korean accents who told me they were from Los Angeles, I didn’t say, “But where are you really from?”, I said, “I’m from San Diego. We’re neighbors!” The thing is, people who reject the answer to “where are you from?” aren’t really asking that. What they really want to know is, “why do you look like that?” What a question! No wonder no one has the audacity to ask it directly. Kim Kimmy had the same kind of experience, being born in one country, raised in another, and now living in third. She dubbed me her “Camino daughter” and gave me much needed life advice.

With a lot to think about, I retired to the municipal and squirted an excessive amount of antiseptic on my feet. It was a cold night. I was fine in my sleeping bag, but Foster only had a liner. I loaned her my puffy jacket to sleep in.

Day 17: Burgos

Evidently the puffy jacket was sufficiently warm because Foster was practically in hibernation throughout the morning while I got the rest of my things together. She was injury free and walking that day. After she left, I found my Dutch friend in the kitchen. She was sick and needed a rest day too, so we went to the front desk and begged for permission to stay a second night in the municipal, citing the pharmacist’s advice that I not walk. They assented as long as we waited a couple of hours after the regular check-in time, which I thought kind of asinine on account of there being more beds than they could possibly fill on a cold, rainy weekday (at least I assumed it was a weekday). Nevertheless, I waited.

And what is the best way to wait when it’s cold and raining and you aren’t supposed to use your feet? You guessed it: sit in a café and blow half your budget on Colacao. Meanwhile, I aired my toes in the cold until they were numb, and then aired them some more.

And I ruminated. I guess I was getting a head start on the mental challenge of the meseta. I second-guessed every major life decision I’d made since my quarter-life crisis began almost three years ago. Some of them I would have reversed in that moment if the opportunity had magically walked in the door. I really would have. Feeling cold, tired, and lonely will do that to your willpower. But those kinds of feelings are temporary, and somewhere inside, between my cold toes and my unwashed hair, the quintessence that is me remembered Oh, the Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Seuss and recognized the truth in it. I was in the waiting place.

No! That wasn’t for me! I knocked off waxing philosophical on children’s literature, got off my melancholy butt, and set off for new heights. Literally. I followed some signs that said “castillo” which led up too many stairs to a castle on the top of a hill. The castle itself was under construction and not worth photographing, but there was a great view of the city and cathedral from up there.

That was as much activity as I could muster for the day. After an early dinner of croquettes that were too heavy for me to finish, I went straight to sleep.

Day 18: Burgos → Hornillos del Camino (20.87 km)

The city was silent in the morning in a way no city in America knows how to be. Only the pilgrims were outside to see the storks wake up on their tall, stone perches and feel the cold finally lift up to a comfortable temperature.

I’d told myself I would walk a relatively short distance and not push myself too hard. In the next small town I stopped at a café/bar for the usual breakfast items and a bocadillo para llevar. Before the edge of town I stopped to rest on some steps with Carrie. She had a reservation at a nice albergue there. Despite the temptation to join her and what I had told myself about taking it easy that day, it was still early and I was itching to keep going.

Just up the road there was a small church. I probably would have passed by it if there hadn’t been a line of pilgrims out the door. Curious to know what was going on, I asked a pilgrim who was just leaving. There was a nun stamping pilgrim passports and giving blessings. I got in line. Where else can you have this kind of experience? It was not a fast-moving line. The nun did not merely bless and stamp in an assembly line fashion; she was not there to reach a quota. She took the time to speak to each and every pilgrim individually. She was a wizened, elderly nun, who reminded me of my late abuela (grandmother) and was so tiny that she had to reach up to put her hand on my head—and I’m only 5 feet (152 cm) tall. When it was my turn she looked into my eyes and asked me (in Spanish) my name, and I told her in my best Castilian accent. She complimented the way I said it and we talked for a couple of minutes. One of the things she told me was that I am very young and therefore have a longer way to walk. I think she was talking more about the pilgrimage of life than the road to Santiago. I’m not really so young as all that, but perhaps my soul is and she could see it. She had an air about her that I don’t know how to put into words. Even now, I cannot seem to think, or talk, or write about her without tearing up. I got the sense that she genuinely loved every single pilgrim. The little pendant she gave me—every pilgrim got the same one—was of the Virgin Mary. I tied it to my backpack where it hung for the rest of my Camino.

After that the terrain became highly reminiscent of the original Microsoft Windows default wallpaper.

Then it went completely flat with nothing but windmills in the distance, leading me to believe that I was already on the meseta. I stopped on the grassy side of the trail to attempt to mitigate the new blisters that were already forming on the bottom of my feet. Someone passing by was regaling a group with the story of the bus replacement from Bayonne to St. Jean. I called after them, “I was on the second bus!” They either didn’t hear me or didn’t care.

My final stopping place was Hornillos del Camino, twice as far from Burgos as I probably should have walked that day. I tiptoed through a cluster of cats into the municipal where I was assigned a top bunk as usual. While I was in the shower (3/10, co-ed, locking stall door, one hook, dirty floor), the ladder from my bunk mysteriously wandered off and was replaced with a wooden stool for me to use to climb up.

The albergue was next to the church and across from a bar/restaurant that blared rock n’ roll music even through mass. Most pilgrims would have been happier if they’d served a communal dinner, but that wasn’t how they operated. They only had five small tables and every group had to put a name on a waiting list. None of my friends were around and I wasn’t in a social mood, so ended up being an awkward group of one. While I was enjoying a good steak and an even better ice cream sundae, I watched the busy waitress run back and forth. She was a Swiss girl who was trying to learn English and Spanish at the same time while everything in her head was in French. She was working so hard that I was determined to tell her she was doing a good job. That’s the kind of thing I often want to do and regretfully fail to follow through with. She was so busy that I nearly lost the opportunity, but on my way out I gave her a poke and told her, and she seemed so glad to hear it.

The rest of the sunny evening—the daylight hours were getting longer and longer—I spent on the church terrace where most of the pilgrims staying in the municipal were hanging out. Word came through the group chat that Teresa and Archer had made it to Burgos and the end of their Camino. I missed them already. One of Teresa’s funny stories would have been great to hear right then. Feeling a little downcast, I chose to read rather than socialize and was slogging my way through Hemingway (not exactly uplifting literature), when there was a sudden commotion and two guys sprinted in the direction of the bar. I moved to where I could see what was going on. A pilgrim had collapsed in front of the bar. A lot of people were already helping and an ambulance was called, and there was nothing I could do other than get in the way, so I sat down on the steps to watch.

While I sat there Thomas from Sweden came and talked to me. He’d noticed I seemed withdrawn and lonely. I kept trying not to cry, but couldn’t help it. He made me tell him what was wrong and I really tried. I awkwardly boiled it down to not knowing what to do with my life, difficulty defying the expectations of others, confusion over whether I’d made good decisions, and guilt over feeling sad when I’ve been lucky and had so many opportunities in life. He was sympathetic. This was his first Camino too and we talked about our impressions and expectations.

Meanwhile, the collapsed pilgrim was lifted and propped up in a chair. The blood on his head was visible from where we sat about 50 feet (15 meters) away, but something else must have been wrong that caused him to fall in the first place. The responders commenced arguing what to do next.

Thomas had a theory that people who do the Camino over and over again do so because they discover themselves or some sense of freedom on the Camino, but when they go back to their everyday life they don’t change anything. He literally called it going “back into the box”. So they have to come back to the Camino to find themselves again. At the time I thought this was probably true. But then I still had more than half of the way to go and a lot to learn.

The loudest and most stressed responder won the argument, and the injured man was laid back down on the ground. The hospitalera who ran the municipal brought a pillow for his head.

We contemplated the meseta and Thomas revealed the shocking truth that we weren’t on it yet. He predicted that the walk across the meseta would be a time when we would look inward and think without distractions and that I would discover who I am. I hoped so; although, at the moment it felt like the more likely scenario was that I would cry my way across it in confusion. Nevertheless, talking to someone helped. I resolved then to think outside of the box about what I really want from life and somehow find the courage to do it no matter what anyone else thinks. That is the hardest thing.

An ambulance finally arrived and the professionals took over. Once they’d loaded the patient into the ambulance, it sat there for what felt like a long time and then drove off back towards Burgos. I never found out who the pilgrim was or what happened to him.

As the sun finally started to admit that it was bedtime, I sidled my way past a volley of scraps that the hospitalera was flinging at the cats, up the wooden stool to my bunk, and into my sleeping bag.

Day 19: Hornillos del Camino → Castrojeriz (19.47 km)

To say I woke up with a positive attitude, ready to seize the day would be a preposterous lie. My eyes thought they smelled onions and didn’t show any sign of changing their mind. I snuck out before anyone could see me, weaving my way through the cats who had formed a militaristic pattern in the tiny foyer, presumably in preparation for an imminent invasion of the kitchen. I left intending to only walk about 10 km, but (spoiler alert) I ended up going 20 km again.

There was a lot of flat terrain again, but every time I thought I must finally be on the meseta, a hill or valley would appear around the bend, and the cuckoo bird would utter its mocking chime.

One of the many pilgrims who passed me that day—I passed no one—was the Spaniard whose backpack had weighed 22 kg in Pamplona. He recognized me and asked about the “Korean guy with the new stuff who didn’t know anything.” I had to admit that I hadn’t seen him at all. As the good-natured Spaniard continued on at a pace I would have had to run to keep up with, he looked back at me and smiled. I was surprised how much I felt cheered up. Then I noticed that he carried only a small day pack and almost laughed.

Later, when I’d just finished airing my feet for the fourth time, Sarah, Emma, Andrew, and Gillian caught up to me. They were cheerful as usual. Sarah chatted with me for a little while about our surroundings. She’d drawn the Microsoft Windows connection too and thought it was pretty. I found the flat bits a little too reminiscent of Oklahoma for my taste. Landscape snobbery aside, Sarah’s smile and the unbreakable good humor of the entire family cheered me up even more.

Somewhere in the middle of the boundless green desert was a café oasis where everyone who’d passed me (so it seemed) was eating and relaxing on the patio. As I staggered up to it with fantasies of orange juice and pastries swirling before my eyes, I was suddenly and swiftly pounced upon by what, at the time, I called a “gaggle” but have since considered to be a “pack” of Aussie nurses who ardently forced their care upon me and refused to take no for an answer. They ordered me into a chair, removed my boots, applied patches of useless Compeed, chastised me for insufficient use of Vaseline, slathered more on my feet themselves, then bought me a glass of zumo de naranja (for which I was truly thankful), and dosed me with 1 g of Paracetamol (Tylenol), the only available painkiller which I’m not allergic to. All the while they vehemently argued with Eliot, a retired Scottish soldier who leads expeditions around the world, about footcare and the proper way to pack a backpack. I think he was actually right about everything, but I dared not go against them for fear of disparaging their profession. If this was their care, I certainly didn’t want to incite their wrath. Then, as quickly as the onslaught had begun, they got up and left, along with almost everyone else. I sat there stunned for a minute or two, with my four cheerful friends as the only remaining witnesses. I wanted to go inside and order more food and get a stamp, but I didn’t. In a daze, I got up and continued walking.

Less than a kilometer down the trail was Hontanas, the town I planned to stop in. It was cute and there were several nice looking albergues/hostels to choose from, including one with a spa. But the painkillers had just kicked in, so against the better judgment of everyone else, I kept walking.

There is a lot to be said for the belief in fate, or that everything happens for a reason, or that you should trust your instincts to take you where you’re meant to be. The path beyond that town where I might have stopped finally induced me to admit that the landscape was beautiful. There were fields of grain that looked almost like soft fur that I wanted to pet, and the breeze rippled its surface like water. I came to a part of the path where I could reach the grain and run my hand over it. It did not disappoint. It really did feel like soft fur. As I was enjoying this sensation, I looked up and saw Foster coming up the trail. She had walked as far as she had time for and was walking back to Burgos to make her way home to London. She said she’d had a feeling she would see me again. If I had stopped earlier, we probably would have missed each other.

Approaching Castrojeriz, the trail passed through some ruins into more rippling fields lined with flowers.

The town itself abutted a hill topped with a ruined castle that loomed triumphantly over the rest of the land. I limped along the cobblestone street expecting to end up in another shabby municipal albergue, when a miracle occurred. I got too tired to continue (that’s not a miracle), so I took a chance and looked into the nearest albergue, which happened to be Albergue Ultreia. It ended up being one of my favorite places I stayed on the Camino. Not only did the owner graciously welcome me in, he gave me a single bed and I didn’t even have to beg or lay siege to it. I took a shower (clean, but still not enough hooks), then hand-washed my laundry to the tune of the serenade of an old Italian pilgrim. And I got my spa experience after all in the refreshingly cold foot soaking tub they had in the rooftop garden.

The pilgrim dinner at Ultreia was the most fun I’d had in days. We were a party of two French, two Germans, two Italians, two Americans (including me), and a Kiwi named Dudley Moore. The food was the usual three courses: vegetable soup and bread, chicken, wine and homemade sangria to drink, and ice cream for dessert. But the real treat was the after-dinner tour of the ancient wine cellar underneath the albergue. Our illustrious guide (the owner) related the history of the place, translating all the important nouns into every language represented and making many “oohs” and “aahs” which we of course echoed through giggles. He let us turn the wine press, then we went down into the cellar where he lit and passed around some twelfth century oil lamps and showed us the old tunnels that used to lead all the way up to the castle. The tour concluded with a tasting of the wine and a toast.

As we got ready for bed, someone got the news that a new pope had been elected and was an American. This was a big surprise to everyone. I don’t know anything about how the pope is selected, but somehow I didn’t think an American would have been allowed. Silly, I know.

My new Italian friends warned me that the real meseta would officially start tomorrow. Based on the foreboding attitude everyone seemed to have about it, I imagined a desolate wasteland resembling Mordor from The Lord of the Rings and mentally braced myself.